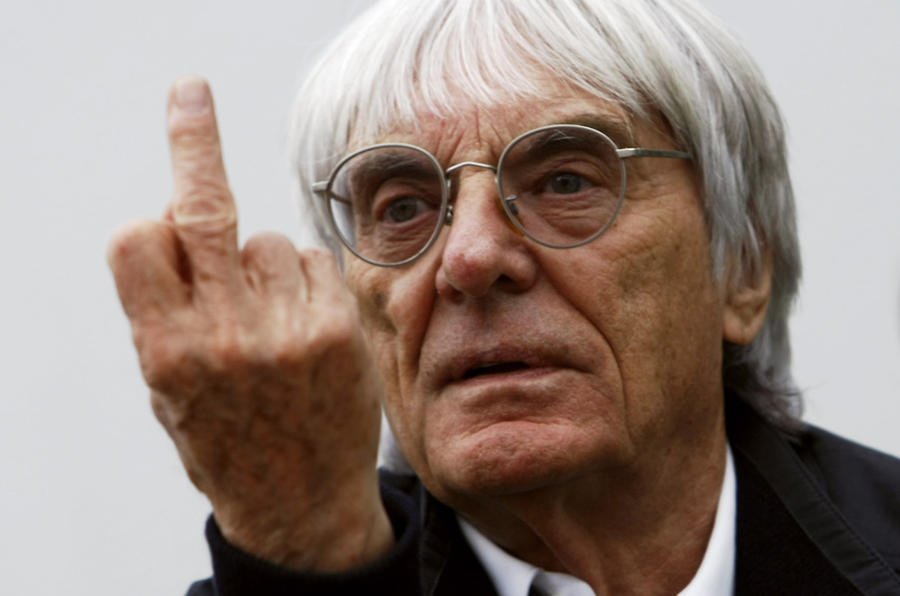

Bernie Ecclestone’s apparent ousting from the helm of Formula 1 has triggered an outpouring of emotions spanning everything from love to hate.

To some degree that’s inevitable. Ecclestone has long revelled in playing the role of a mischievous rogue, albeit with a willingness to abandon the mischief for downright ruthlessness if there was a pound sign at the end of the deal.

Here are some quick-fire thoughts that could guide where the pendulum of opinion should settle - and please feel free to leave some of your own ideas below.

Love him

Bernard Charles Ecclestone is the son of a trawlerman who grew up in a tough part of London and who left school at 16. The boy’s done good.

He was smart enough to stop racing rather than pursue the dream of making it behind the wheel. Reports vary, but the word is he was a decent-enough driver if not a top-rate one, and he attempted to qualify for the Monaco Grand Prix, albeit unsuccessfully. You have to be smart to walk away from what you love.

After turning his hand to driver management, he twice displayed a level of humanity not normally associated with his public image today. After driver Stuart Lewis-Evans was killed, Ecclestone retired from racing, because he was so badly shaken. Likewise, when his driver Jochen Rindt was killed (subsequently winning the F1 title posthumously) he was deeply affected, and legend has it he ensured Rindt’s family was properly looked after.

He saved the Brabham F1 team, buying it in 1972 and owning and nurturing it for 15 years, winning two driver’s championships and nurturing the careers of Niki Lauda, Nelson Piquet and Gordon Murray. He remained intensely loyal to trusted members of his team thereafter.

Formula One would not be the global mega-sport it is today without his vision and foresight, not to mention his ability for holding together a disparate group of teams, promoters, circuits and more. His tactics may be brutal at times, but few can argue with the outcome.

At his best, he was brutally, hilariously honest. For a time he was part of a consortium that owned Queens Park Rangers football club, although nobody was sure why, least of all himself. “I leave at half-time,” he explained. “By then you can see which way it's going. If you ask me to name five of our team, I couldn't. All bloody nice guys but I don't mix with them so I don't know them well. I don't go in the dressing room. They can walk out of the showers and I feel I've got an inferiority complex.

”

McLaren F1 CEO Zak Brown: next year will be a 'game changer' for the brand

He didn’t like lawyers, and nobody but lawyers likes lawyers. “If you say 'good morning' in America and it's five past twelve you end up with a lawsuit,” he once said, perfectly summing up his position.

Join the debate

Add your comment

Silverstone v Abu Dhabi

Bernie Ecclestone: should we love him or hate him?

F1 ?