Performance Plus 105kWh Turbo Saloon 4dr Electric Auto 4WD (11kW Charger) (884 ps)

Submitted by dev_editor on

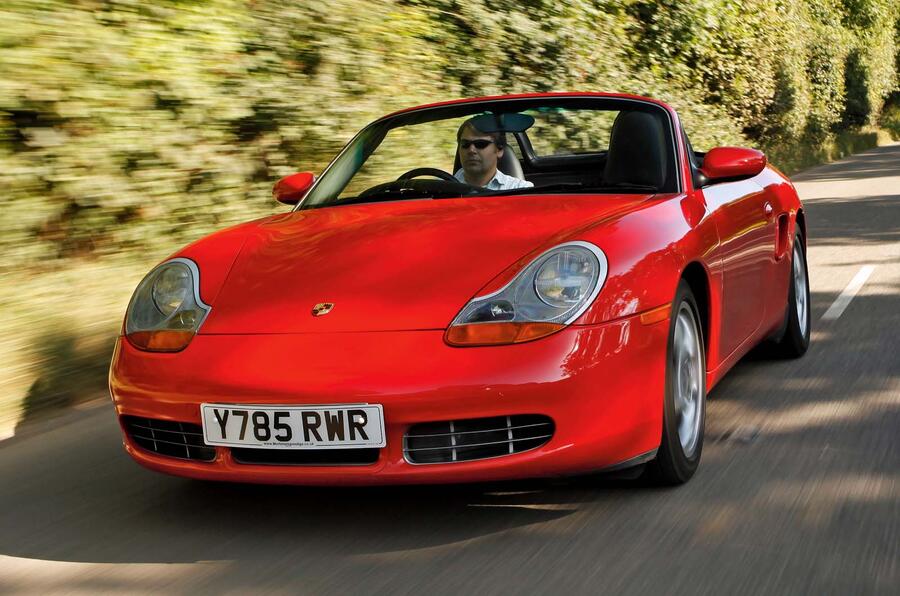

On driving pleasure per pound spent, an early Porsche Boxster has to be a front-runner right now.

You can buy a distantly-travelled, base 2.5-litre-engined 986 for little more than £4000 these days, and while that might be a pool to dip into with caution, you don’t have to spend a heap more to get a car that’s a long way short of 100,000 miles.

For your money you get a Porsche flat six for starters and yes, it will wail your neck hairs to attention if you exercise it hard enough. It sits right behind you, of course, so that your Boxster seems to pivot from a point deep beneath the handbrake, its main heft located for optimal direction changing.

More optimal than big brother can naturally deliver in fact, the flat six shifted rearwards in the interests of 911 tradition and the provision of an extra pair of seats. The Boxster’s steering wheel swivels with oiled, well-measured resistance, it twitches in sympathy with the topography beneath, and vibrates as the front tyres break their grip if you’ve pushed it hard enough. In other words, you get real feel at the rim.

You’ll also enjoy a low-roll, forgiving ride, firmly potent brakes, a solidly slicing shift and a feelsome clutch, all the controls melding and blending in a way that confirms this car’s breeding every time you drive it. Even to the shops.

Few cars offer such tactile pedigree for so little money. One reason these Porsches are relatively cheap is that they’re relatively old, the youngest 986-generation Boxster now 15 and looking slightly dowdy because it’s gone out of fashion. That also means that some are looking tired and a little unloved now.

There’s another reason for the low prices, and it may well be familiar, this the much scribbled-about issues with the Boxster and the 996-generation 911.

Cylinder liner cracks, the destructive failure of the intermediate shaft bearing and leaky crankshaft main oil seals are the risks, the first two potentially very expensive. But mitigating modifications can be made – if you have them done when the clutch is changed you’ll get better value from the gearbox-out labour bill – and the pre-2000 Boxsters use a more durable intermediate shaft bearing.

The problems actually occur pretty rarely, and quite a number of cars may have been modified, but there’s no doubt that these threats reduce Boxster prices. An engine rebuild will almost certainly cost more than the car is worth.

Which gives you the intriguing possibility of running a cheap Boxster until its engine blows. Which it may never do, of course, but equally, you could be looking at the smoking ruin of a flat six mere hours after you bought the car. In which case your chosen descriptor of the situation might not necessarily be “intriguing”. That would be an unlucky outcome, and in most other respects the Boxster is a pretty robust machine. It’s certainly not prone to corrosion.

Spend more, buy a lowish-mileage car with a fat sheaf of Porsche and specialist bills and you might be looking at an investment, or at least a low-cost classic that will be nothing short of a joy to drive. That early Boxsters will be sought after is surely guaranteed.

The new Porsche 911 Turbo S features a hybridised flat six that pumps out more power than any version of the sports car so far.

Electrifying the Turbo S is the most significant change to the model’s technical recipe since a second turbocharger and four-wheel drive were introduced in the mid-1990s. The move pushes Porsche’s flagship road car beyond the 700bhp mark, with a corresponding increase in price.

The hybrid Turbo S will start from £199,100 in coupé form, with the cabriolet costing £10,000 more. First deliveries are expected in late 2025.

A non-S derivative is so far unconfirmed – and may never come, reflecting the fact that in modern times the maximalist S has been the stronger seller.

While this 992.2-gen model is technically a mid-life facelift for a car that has been on sale since 2020, the changes under the skin are wide-ranging. The 3.7-litre flat six of the outgoing 911 Turbo S is replaced by a version of the 3.6-litre engine found in the 911 Carrera GTS hybrid, with the same asymmetric valve timing but new pistons for a higher compression ratio. It also has an additional ‘eTurbo’, with the car’s two blowers working in parallel.

The upshot for this second electrified version of the 911 is 701bhp between 6500rpm and 7000rpm (versus 641bhp at 6750rpm for the old Turbo S) and 590lb ft of torque at 2300-6000rpm. Torque is no higher than before but its scope – what engineers refer to as the area under the curve – is vastly greater than that of the previous Turbo S, no doubt making for even more wild point-to-point performance.

Porsche’s T-Hybrid system uses a 1.9kWh battery ahead of the scuttle to drive an electric motor connected to the shaft between the compressor and turbine wheels in each turbo. This allows the turbos to spool up extremely quickly and reach peak boost “about two seconds” sooner than otherwise, curtailing lag. It gives the new Turbo S unprecedented throttle response.

The battery also feeds an electric motor in the reinforced eight-speed PDK gearbox, further sharpening throttle response by injecting up to 139lb ft into the driveline before the flat six hits its stride.

Once the turbos are at the desired level of boost, the motor is used to regulate the speed of the shaft. In doing so, it can harvest energy, sending it back to the battery or directly to the slim e-motor in the gearbox, which can also feed the battery during deceleration. It is an entirely closed system so the 911 Turbo S isn’t a PHEV.

The claimed 0-62mph time is 2.5sec, but that closely matches Autocar’s road test time for the old model so expect what is the most potent production 911 in history to do even better. The official top speed is slightly lower than before, though, at exactly 200mph.

Elsewhere, the new Turbo S sports wider, 325mm rear tyres and larger rear brakes. Carbon-ceramic discs and rear–steer are standard. A two-tier rear spoiler-cumwing and a deployable front splitter remain, but the new car has further active aero via the gills in its front bumper.

The cross-connected active anti-roll bars are also now electrohydraulic, courtesy of the new 400V circuit, and can actuate much quicker than before.

The exhaust system is titanium, saving 6.8kg, while wiper arms made in a composite are 50% lighter. However, the total weight of the car has increased by 85kg to 1725kg – although that is with the optional rear seats in place.

On the test track at Weissach, Germany, a pre-production Turbo S, hot from exertion, peels into the pit lane and sets itself for yet another launch control start.

This time round the driver, Jörg Bergmeister, delays his release of the brakes and for a moment, as the engine is held at 5000rpm and surplus boost pressure furiously bleeds out of the T-Hybrid powertrain, the car roars like a Boeing 747 during static takeoff. Then it seemingly disappears: poof! The new Turbo S might not sound all that romantic but it isn’t in any sense lacking in drama. Its no-holds-barred tech slant also gives it the aura of a reincarnated 959.

A few minutes later, it’s my turn in the passenger seat. I clock the new ‘Turbonite’ detailing inside the updated cabin before Bergmeister releases the bungee cord. It’s tricky to appreciate anything when you’re subjected to this level of longitudinal g but the engine note, now lightly enhanced by the rear speakers, is more serrated than before.

As the laps unfold, it’s obvious that the Turbo S’s limit handling is enhanced by the T-Hybrid system. The performance is also absurd, even on cooked Pirelli P Zero R tyres. On this technical track, even a 911 GT3 RS couldn’t keep up.

“You don’t have turbo lag any more and therefore you don’t drive it like a Turbo,” says Bergmeister while countersteering within a few feet of the Armco. “I drive it like a normally aspirated car, positioning it with the throttle and just playing with it. It’s much more satisfying than always having to anticipate the turbo lag and hoping to get it right.”

Whether all this translates to a more engaging, rewarding road car driven at sane speeds is something we’ll discover later this year, but it seems likely.

The 1990s were a time of great speed. As marathon-ready trainers became everyday footwear and hard-and-fast house music pulsed through city streets, it seemed a given that even the most snooze-worthy family hauler would be reheated into a have-a-go hero.

Sierra Sapphire Cosworths and Lotus Carltons hit the headlines as the joyriders’ favourites - eminently nickable and so fast the fuzz couldn’t keep up. Japanese manufacturers finally stamped their mark on the performance car scene, undoubtedly helped along by the immense popularity of Sony’s game-changing Playstation and the Gran Turismo series.

And, as if we didn’t already have it good enough, we witnessed a speed war between Jaguar, McLaren and many more besides. So revered were those cars that a great many of the ‘90s’ motoring highlights are now well out of reach.

What was once a £20,000 Honda NSX is now an £80,000 garage queen. Lancia Delta Integrales can push six figures, and even the common man’s Ford Escort RS Turbo is £20,000.

That isn’t to say there aren’t bargain superstars out there, however. Here are some of the best…

A howling flat six, super-sharp steering and stunning wide-hipped looks – they can all be yours from just £3000. Of course, the cheapest Boxsters are best avoided, but the truth is that these are surprisingly hardy little roadsters – provided you buy carefully.

Its best-known Achilles is the intermediate-shaft (IMS) bearing, which in some cases fractures or even shatters after a long and hard life. This then throws off the engine’s timing and shunts pistons into valves, requiring a really rather expensive rebuild.

Thankfully, many examples’ bearings have already been replaced, and typically with a sturdier aftermarket item that isn’t prone to exploding. If it hasn’t been done, add another £800 or so to the car’s price, if you get it done alongside a new clutch – which you probably should.

It’s also worth checking the immobiliser, locks and alarms work as intended: blocked door seals or a leaky roof can mean the ECU (located under the driver’s seat) gets wet and dies. Replacements are £500-plus.

Still, it’s easy to snag a good ’un – and you absolutely should, before prices soar.

Volkswagen’s junior coupé was always a tidy steer, but its full potential wasn’t unleashed until 1992. The fitment of a potent 2.9-litre narrow-angle V6 made it the fastest front-driver of the day, and it somehow improved the handling compared with the smaller (but turbocharged) four-pot.

Every Corrado was made from galvanised steel, so they hold up better against rust than many rivals – and it’s a good indicator of a dodgy repair, which should be easy to spot.

High-milers go for around £6000, but you shouldn’t be scared off by that: these are generally reliable bona fide modern classics.

Early Calibras were tarnished with a reputation for being a bit too much like the Cavalier on which they were based. The 4x4 Turbo flipped that notion on its head, turning what was a slightly humdrum coupé into Britain’s cheapest 150mph car.

Today, though, they’re an expensive window onto the past, with prices venturing well into five figures.

This was the car that really put the Type R name on the map when it landed here in 1998, thanks to an all-time-great engine and tremendous handling. Clean cars go for about £15k, but it’s also worth considering importing one from Japan while the yen’s value is low.

“Nasty steering, a vague gearchange, dubious handling and dead-feeling brakes,” we said back then, pulling no punches. The 220 may not be a good car to drive, but it has an intangible appeal as the plucky underdog.

These are now incredibly rare and prices vary wildly, but around £5000 should be enough to secure one in mint condition.

“The hardest-hitting, least compromised all-rounder on sale for less than £30,000,” is what we reckoned of the 328i back in 1995. Much of the same remains true today, except you can snag one for one-tenth of the as-new asking price.

Many have led hard lives, though – these were sub-£1000 cars for a long time – so buy carefully.

A Chris Bangle masterpiece, and not half bad to drive either. The five-cylinder 20-valve engine, offered in both naturally aspirated and turbocharged forms, has the most exotic feel, but the four-cylinder option, a descendant of the Delta Integrale powerplant, still has the means to entertain.

Rust is by far the biggest issue: inspect the sills, subframes, wheel arches, footwells, boot floor, exhaust… Basically, just give the whole thing a thorough going-over. Interior plastics are prone to developing a horrid sticky finish, too.

Running project cars can be found for £500, but the best examples are north of £10,000.

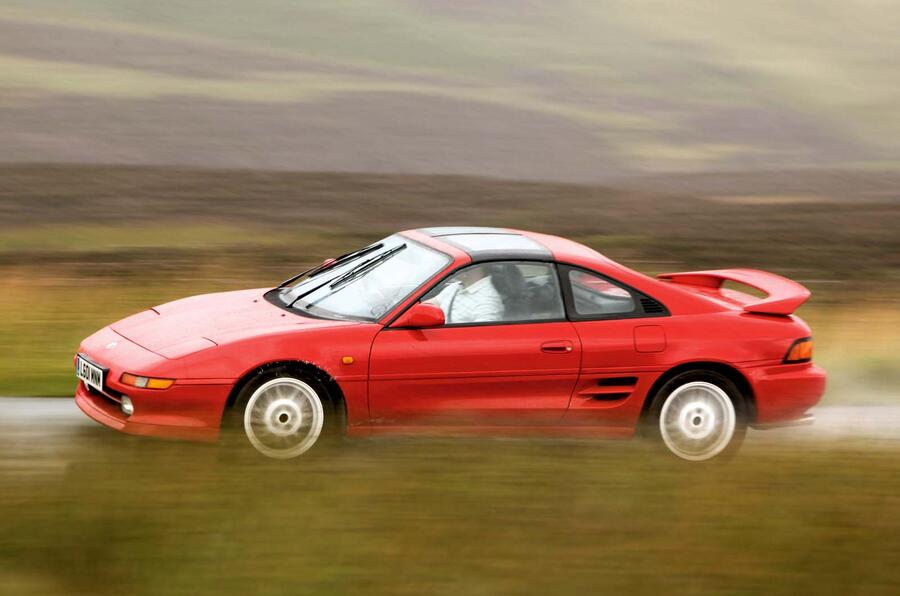

Forget the second-generation MR2’s reputation for having a wayward tail – we never thought that held very much water. Still, Toyota revised the model no fewer than five times, with updates two (in 1991) and three (1993) gradually softening the handling to tune out the risk of snap oversteer. Any MR2 is a great drive and a fairly reliable proposition, barring rust or any extensive modifications.

It’s worth seeking out a Japanese-import Turbo model or one with the atmospheric ‘Beams’ engine that came with Yamaha-developed cylinder heads; either example brings with it the soundtrack and performance the car’s chassis and looks deserve.

Such cars will set you back around £10,000.

The Twingo has aged like Mr Blobby: once a tad unsightly, but now remembered for flouting convention and embracing the absurd. In the Twingo’s favour, it didn’t single-handedly traumatise a generation of children, so it’s looked back on a bit more fondly.

You can occasionally find them from £5k, but it’s perhaps easier to source and import a clean car yourself.

If it’s a pure driver’s car you want, look elsewhere. But the Z3 has otherwise aged tremendously, with long-nosed, low-slung proportions and – as long as you go for the 2.0-litre engine or bigger – some of BMW’s greatest straight-six lumps.

Prices – from £1000 – are on the up, so now is the time to buy.

“The GTi is back,” declared our road testers after sampling the performance-enhanced 306. For years, hot hatchbacks had been iced over, hamstrung by horrendous insurance premiums and the looming threat of theft.

But the French machine’s combination of a 167bhp four-pot (then one of the most powerful engines to have featured in a hatch), a six-speed gearbox (when most rivals made do with five ratios) and a simply stunning chassis raised the bar. Suddenly, the race was back on.

Avoid track-converted cars; clean examples should start at £5000 or so.

Technically speaking, the R129’s life started in the late 1980s, but the fourth-generation SL didn’t really hit the limelight until a few years later. Its sheer desirability – thanks in no small part to those futuristic lines and stonking £50k-plus price tag – made it the darling of the burgeoning hip-hop subculture.

And if you can picture yourself rollin’ in a 500 Benz, just like Tupac, the good news is that SLs are today shockingly affordable. Just £3000 gets you behind the wheel of a ropey car, but we’d budget £10,000 or so for something more dependable.

Engines ranged from a 2.8-litre V6 all the way up to a 7.3-litre V12 fettled by AMG (good luck finding one of those), but our pick was the grunty 5.0-litre V8, badged 500 SL. Look out for an original car with a good service history, and you shouldn’t encounter too many issues.

A hard-top roof is a desirable extra for the colder months, but the standard soft-top should prove adequate, providing it’s been properly looked after (or replaced in the relatively recent past with an official Mercedes-Benz part).

Hot hatches are nothing new, but it’s rare that the treatment proves to be the redemption story for what was otherwise a generational stinker.

So it proved, however, for the maligned Mk5 Escort, transformed by a fizzy 148bhp twin-cam four, quicker steering and a chassis overhaul. The addition of four-wheel drive in 1994 only raised its limits, making it a genuine Cossie-lite. As remixes go, it’s tantamount to The Prodigy turning a kids’ safety ad about not talking to strangers into a rave classic.

Not cheap today, though: expect to pay about £8000 for a good runner.

All the joy of the 306 GTi, but in a smaller, lighter and slipperier package. The 106 GTi was as close as Peugeot ever came to properly replacing the 205 GTi, and today a good example can fetch a five-figure sum.

At that price, though, you should also consider the 106 Rallye, which went without power steering and much of the cabin kit in pursuit of pure driving thrills.

The Focus was the car that righted all the later wrongs of its Escort predecessor and democratised the attributes of all the best driver’s cars. Ignore the ST and the eye-wateringly expensive RS, and instead look for a tidy Zetec petrol that has managed to elude the tin worm.

Just a few thousand pounds should snag one you can enjoy for years to come.

Munich’s Icarus was too heavy and too blunt in its responses to be a proper grand tourer, and it cost around the same money as Mercedes’ SL. But in 1993 the tide began to turn with the introduction of the 850CSi.

It was an M car in all but name, with its V12 engine upsized and boosted to a hearty 375bhp so the 8 could finally provide a driving experience that lived up to its gorgeous looks.

It’s also worth considering the later 4.4-litre 840Ci, which finally felt like the 8 Series had become a proper GT car. Prices for the 8 Series start at around £10,000, but CSis are now hitting £50,000-plus.

Submitted by dev_editor on

Submitted by dev_editor on